1910-1919

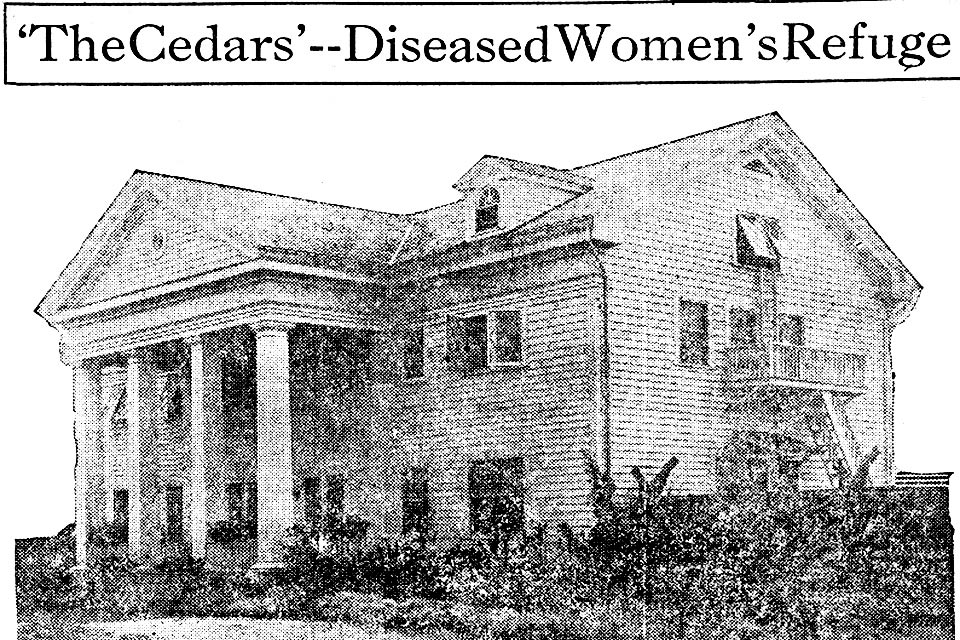

The Cedars was a City of Portland facility established in the 1910s on the poor farm property.

Read More

Its mission was to "rehabilitate" sporting women. In the mid-1920s, The Cedars was reincarnated as the Bealey Military Academy, and then a decade later, dismantled and rebuilt as the building that today houses Ruby's Spa.

1911

Construction of the grandiose main lodge of the Multnomah County Poor Farm took place through much of 1911 and required an army of craftsmen.

1930's Mid

This mid-1930s aerial shows the county poor farm complex at its height of operation during the Great depression when over 600 people were happy to call it home.

1931-1963

Chris Boyd may have had the longest residency of any poor farm resident, 1931 to 1963.

Read More

Because he liked to sit and rock on the front porch, Chris assumed the role of Edgefield's unofficial greeter for much of the three-decade period.

1937

This building was constructed in 1937 as the poor farm cannery.

Read More

In 1991, it seemed the natural space for McMenamins Edgefield's brewery, which is still the company's largest.

1950-1959

Today, thousands come to Edgefield to see performances on the east lawn. In years past, events were a more cozy affair.

Read More

In years past, such events like this one in the 1950s, were a more cozy affair. A rare snowfall proved a good reason to photograph the poor farm during a prosperous period of the 1950s. Note the bus parked in front of the side porch.

1960's Mid

Del Stoffer, Edgefield's last farm manager, sits astride his horse outside the west porch, mid 1960s.

1969

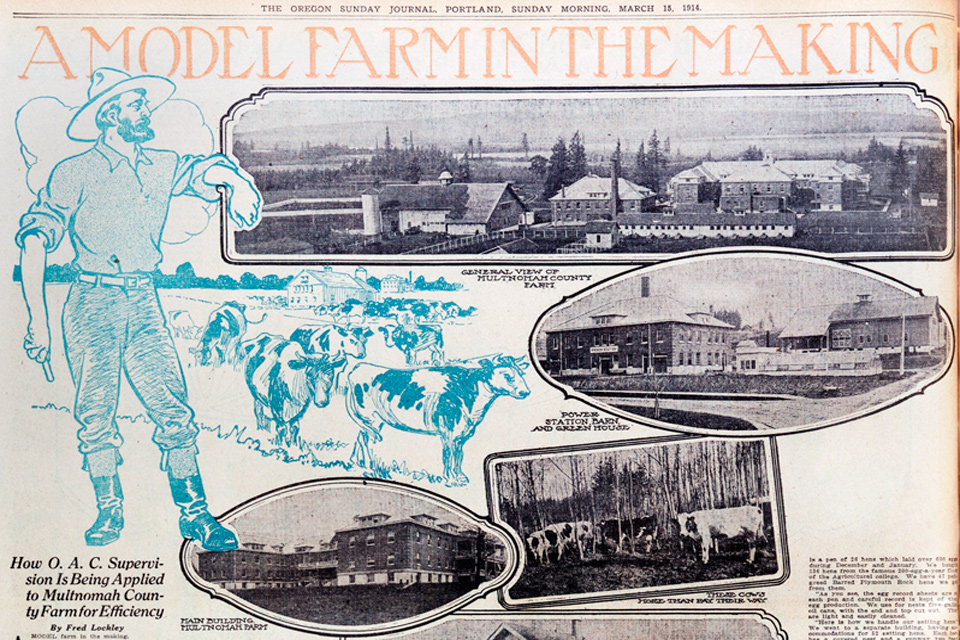

The Multnomah County Poor Farm was hailed as a model of agricultural efficiency and production.

Read More

The Multnomah County Poor Farm was hailed as a model of agricultural efficiency and production. It provided food not only for poor farm residents, but also those of the county jail and hospital. The farm operation finally ceased in 1969.

1980

A deep source of regret for McMenamins was the loss of great barns of the poor farm.

Read More

A deep source of regret for McMenamins was the loss of great barns of the poor farm. Fearing injuries and lawsuits arising from the teenagers roaming the property largely unchecked during the 1980s, the county had the well-preserved barns torn down shortly before Mike and Brian bought the property. Here is the milking barn as it looked in 1980.

1980-1989

Wild blackberries consumed much of the Edgefield property during its vacant period of the 1980s.

Read More

Wild blackberries consumed much of the Edgefield property during its vacant period of the 1980s. Entire outbuildings disappeared. Here the old greenhouse is threatened. The tangled quagmire in the foreground is where the present herb garden is laid out.

1989

After several years of neglect and vandalism, the abandoned poor farm appeared better suited for a wrecking ball than a rehabilitation.

1990

The first step of McMenamins' revival of the old poor farm was good, old-fashioned cleansing, performed of course by a pipe and drum band.

1990-1999

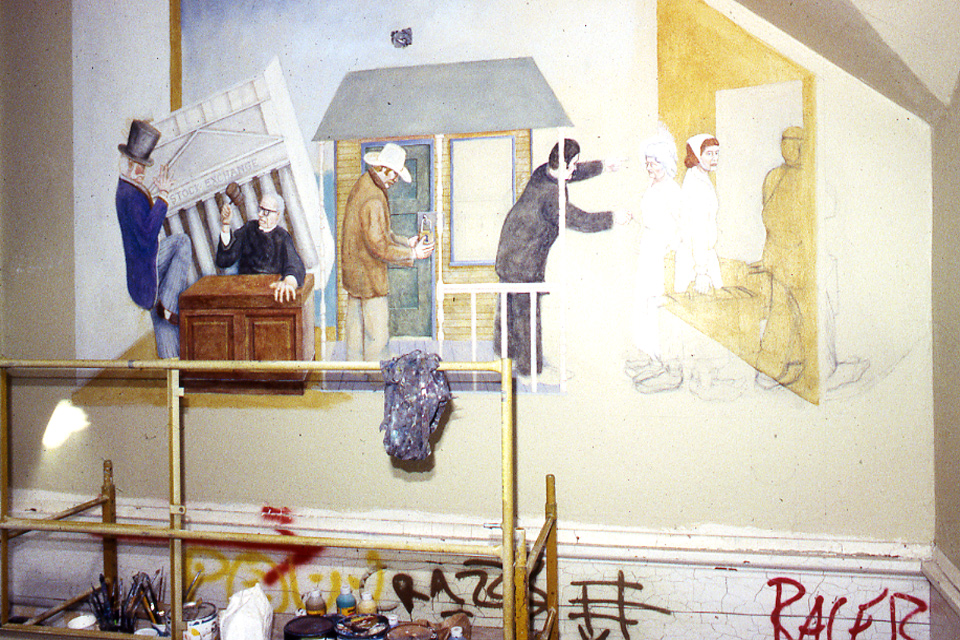

As part of McMenaminss' 1990s renovation, a team of artists enlivened the old farm with bits of the property history.

1990's

Gardens were part of McMenamins' initial rejuvenation of Edgefield in the 1990s.

Read More

Gardens were part of McMenamins' initial rejuvenation of Edgefield in the 1990s. Here the herb garden is being laid out on the north side of the greenhouse. Vintage photos show that a flower garden was in this same spot in decades past.

1990's Early

The early stages of McMenamins' renovation included the hauling away of many dumpsters' worth of rubbish and debris.

Read More

The early stages of McMenamins' renovation included the hauling away of many dumpsters' worth of rubbish and debris. In the early 1990s, McMenamins removed this transformer to make room for the outdoor dining and event area known as the Loading Dock. The transformer was memorialized in one of the earliest brews made at Edgefield, called Transformer Ale.

1991

Reconstruction of the burned-out Power Station and fashioning a pub, movie theater and lodging rooms.

Read More

Reconstruction of the burned-out Power Station and fashioning a pub, movie theater and lodging rooms within the original 1911 structure came in 1991. The brewery McMenamins created at Edgefield in 1991 remains the company's largest.

1998

"We took what was there at Edgefield and tucked a golf course into it."

Read More

"We took what was there at Edgefield and tucked a golf course into it." Thats's how Patrick McNurney explains the original layout for the Pub Course. Patrick helped in the courses's design and construction. At the debut of the course on August 31, 1998, Mike McMenamin sunk his first hole-in-one ever.

At Edgefield, during its seven-decade run as a poor farm, a remarkable array of personalities congregated under its roof: sea captains, captains of industry, school teachers, ministers, musicians, loggers, nurses, home builders, homemakers, former slaves and slave owners. There were Germans, Italians, Japanese, Chinese, Native Americans, African Americans; Catholic, Protestant, Muslim, and Buddhist. Frankie of "Frankie and Johnny" notoriety was there. The one common thread among them was, at one time (and perhaps others) in their lives, each needed a "leg up."

Many of the residents, or inmates as they originally were called, supplied the labor for the 300+-acre farm. Overseen by a succession of well-seasoned, college-educated farm supervisors, Edgefield was a model of agricultural efficiency and production. The fruit, vegetables, dairy, hogs, and poultry raised on property was sufficient for feeding the population at the poor farm, as well as the county hospital and jail. Many years, surplus quantities were canned and sold on the open market.

Perhaps the greatest challenge for the farm supervisor was maintaining an adequate and capable labor force. Field "workers" were constantly coming and going and of course none were hired for their farming expertise. Outside labor gangs were periodically contracted-farm students, prisoners, prisoners of war, even some of Oregon's first Braceros (migrant workers from Mexico)¬-to supplement the on-site force.

The Great Depression was one notable period when the labor supply was not an issue. In the early 1930s, when so many people needed "legs up," Edgefield's population swelled to over 600, nearly double its normal number. Closets were converted and residents put three or more to a room in an ongoing effort to accommodate the great demand. The poor farm's basement quickly emerged as a veritable bazaar made up of booths operated by the legions of unemployed craftsmen and artisans living upstairs. The pool of talent and services available in those basement booths drew faithful patronage from Portland customers.

In the 1940s, when World War II put Americans back to work, Edgefield's population shrank considerably, and those who remained were many Depression-era residents who had reached an advanced age or state of incapacity to prevent their departures. To better suit these needs, in the Post War years, Edgefield took on more of a role of a nursing home and rehabilitation center, though the farm operation continued through the 1960s.

In the 1970s, Edgefield saw fewer incoming patients as private nursing homes and in-home care became more accessible with the rise of Welfare and Medicaid. A shrinking population and a complex of aging buildings in need of daunting repairs forced the decision to close the old poor farm. In April 1982, the last patients were relocated and the place was locked up, though not too securely.

For the remainder of the 1980s, the elements and vandals¬-mostly bored teenagers¬-wreaked havoc on the property. Burst pipes sent water everywhere, windows were broken, every surface was spray painted with graffiti, and everything not bolted down was stolen. The place that for decades had been a refuge for thousands of needy souls was now a liability to the county. Arrangements to demolish the building were put in place.

It would have happened, too, if it weren't for those pesky Troutdale Historical Society folks who decried such a move a "foul and unjust fate!" These courageous and resolute history-minded folks waged a five-year fight to save. Once victory was theirs, however, the bigger battle began: Who wants an old poor farm, anyway? A listing with a New York auction house prompted exactly no bids.

Enter brothers and Portland sons, Mike and Brian McMenamin. Amongst the ruins of Edgefield they saw a fabled gathering spot, a village populated by artists, artisans, gardeners, craftspeople, musicians, and folks from surrounding communities. The people holding the purse strings didn't see it.

General confusion reigned amongst the moneylenders. They felt Mike and Brian's proposal was a somewhat vague and decidedly different direction for the brothers, who to that point had opened a handful of neighborhood pubs in the Portland area. By 1990, though, the pair had developed a pretty good sense about the philosophy and verse of pubs, having opened their first in 1974.

On their journey of discovery, the brothers' definition and expectations of a pub broadened. At the absolute core is a welcoming gathering spot for people of all ages. It needn't depend on trendy décor; rather the people who have gathered and their conversations create the finest atmosphere (though, good music, good beer and good food often will enhance the experience). From this core, radiated such new rays as breweries, movie theaters, lodging rooms, artwork and history. But all this proved to be just a foundation for what a pub could be.

Braced with some experience, brimming with ideas and enthusiasm, and given a proverbial blank canvas with Edgefield, all that was needed was financing. The money finally came when two separate banks agreed to loan the brothers enough to accomplish the first stage. When (if?) that was completed, additional funding would be forthcoming. WaHoo!

First came the winery, in 1990. The following year saw the opening of a brewery, and the Power Station pub, movie theater and McMenamins first venture into lodging: eight rooms. Through word of mouth and minimal advertising, people started to come-despite the property's then remote location on a county road, 16 miles distant from the company's Portland customer base.

And the people came, the McMenamins' faithful, disciples of the then-raging Microbrew Revolution. They were curious about this big new adventure, tolerant of the tumble down condition of the rest of the property, and thirsty for a good brew!

This initial spurt of success allowed the adventure to continue: renovation of the main lodge into hotel rooms, specialty bars, a fine dining restaurant, and inventive event spaces. Also, wondrous gardens, artisans shops, concerts, big and small, and golf.

Every salvageable building, shed, and outbuilding of the old poor farm that could be found beneath the rampant wild blackberries was saved. The mechanics facility became a festive event space called Blackberry Hall. The root cellar-turned stable found new life as the Distillery and clubhouse for the golf course. The delousing shed was reborn as the Black Rabbit House bar. Even the poor farm incinerator got a creative transformation into the Little Red Shed, prototype of McMenamins' long line of small bars to follow.

A blending of art and history has become another of the property's attractions, another McMenamins' first that germinated at Edgefield. A team of more than a dozen artists was turned loose on the place, armed with tales and photos of the poor farm, its residents, and the surrounding area, with the directive to celebrate the rich past while doing away with the property's institutional feel. Now, it's hard to find a surface not enlivened by an artistic flourish and nod to the past.

McMenamins Edgefield continues its emergence as a pub of a most delightfully broadened definition, a village of artisans and publicans. The ever-evolving mélange of personalities, events, landscape and architecture makes for a truly extraordinary setting, inseparable from its poor farm past, and soon to be augmented by new lodging rooms in the 1962 county jail facility, and who knows, maybe a 360-degree bar in the old farm silo.